By Sheeva Azma

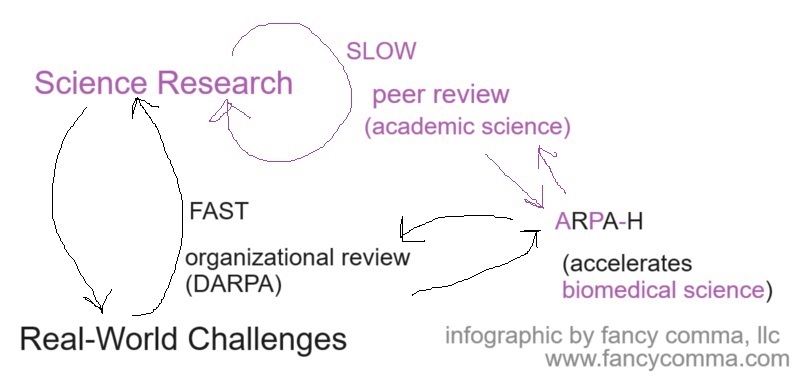

Peer-review and organizational-review research models are two different research paradigms. Used together, they ensure that research is not only rigorous but can address emerging global challenges.

Tweet

Research and development, or R&D, refers to the work undertaken to develop new innovations and technologies for cultural and societal benefit. The United States is a leader in R&D funding. In 2020, the US spent approximately $717 billion in science funding. To give that number some context, the whole world spent $2.4 trillion investing in R&D funding in 2019, so US R&D spending in 2020 was about 30% of the global R&D spend.

The US model of science relies heavily on federal support

The science funding system in the United States, as we know it, was conceptualized by the first US presidential science advisor, Vannevar Bush. President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Bush to lead the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) in World War II. As the OSRD director, Bush oversaw the US’s wartime science research, such as the Manhattan Project and the development of radar technology.

Bush’s idea of science was one in which the government funded science to yield new discoveries to help advance society. In turn, the federal government also played a role, in Bush’s mind, in establishing a science-literate workforce. In his book, Science, the Endless Frontier, Bush writes: “The Federal Government should accept new responsibilities for promoting the creation of new scientific knowledge and the development of scientific talent in our youth.” It was Bush’s idea to establish the National Science Foundation, or NSF, which President Harry Truman did in 1950.

There’s no single R&D agency in the US!

There are many federal R&D agencies in the US; beyond the NSF, there is also the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the national labs, and research going on in many federal agencies. The lack of a unitary federal R&D agency in the United States poses challenges to coordinating collective efforts to promote progress and innovation. The decentralized, mission-oriented nature of science funding means that priority-setting for science and technology policy can be challenging. Research programs can be fragmented, and are dependent on annual appropriations bills, which must be drafted, and voted on, by Congress every year.

In a typical fiscal year, funding approved by the legislative branch is distributed to multiple R&D agencies. Accordingly, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issues a memorandum in cooperation with the Office of Management and Budget; this memo articulates priorities for R&D funding across agencies. While the OSTP has no budgeting power, it works to establish interagency programs which address the nation’s science and technology priorities.

“Slow” vs. “fast” science

A primary goal of science research is to maintain competitiveness in the global economy. To this end, government research agencies employ both peer-review and organizational-review mechanisms to fund research which may ultimately generate economic prosperity through applications of scientific breakthroughs. Peer review is a slow, anonymous process used in most academic communities, including science, to evaluate new ideas and claims. In this process, grants are evaluated anonymously by peer scientists trained in the nuances of the research. Peer review emphasizes accountability, keeping cronyism and conflicts of interest to a minimum, and is the gold standard at basic science and biomedical research agencies such as the NIH and NSF, as well as in journal articles.

While peer review emphasizes scientific rigor, organizational or “chain-of-command” review emphasizes intellectual risk-taking in research projects. Organizational review is a hierarchical structure whereby technology drives new technology. Organizational review is employed in the defense sector by agencies including the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and is notable for its relatively quick turnaround. Intellectual risk-taking is necessary to maintain the United States’ technology at a level comparable to innovations of international counterparts, to avoid technology “surprises” from other countries. We use many DARPA inventions every day. The invention of the Internet, for example, was an innovation leading directly from DARPA projects.

ARPA-H combines slow-track & fast-track research

The pandemic created a new type of “fast-track” research, in which peer-review and organizational review are combined. Operation Warp Speed combined academic peer review and federal regulatory mechanisms with organizational “chain-of-command” review by uniting government, including defense sectors, as well as industry, to align resources to accelerate the production of COVID vaccines. Using these two paradigms together to bring de-risked, high-reward therapeutics and vaccine science to fruition for society proved useful.

On March 15, 2022, President Biden established ARPA-H, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, to apply some of the health research lessons learned by combining fast-track and slower research mechanisms. Modeled after DARPA, ARPA-H’s goal, as stated on the ARPA-H website, is to invest in research “for real world-impact.” This includes R&D for potentially transformative “platforms, capabilities, resources, and solutions” in health and medicine “that cannot readily be accomplished through traditional research or commercial activity.” While ARPA-H is formally part of the NIH, the director of ARPA-H reports directly to the Department of Health and Human Services, the NIH’s parent department. Therefore, its organizational structure includes a mix of fast-track and slow-track elements. For more on how ARPA-H works, check out this report from the US Congressional Research Service.

Using science to solve tough problems

The United States faces challenges on such issues as clean alternative energy development, job growth, national security, advanced semiconductor manufacturing, staying one step ahead of the next pandemic, educating the next generation of STEM workers, and more. Together, the paradigms of peer and organizational review foster a dynamic research environment encouraging both fast-paced innovation and academic rigor to surmount these and other 21st-century issues.

6 thoughts on “Models of US Science Research & Development”