By Sheeva Azma

On November 14, 2024, the Pew Research Center released a report entitled “Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking.” You can check it out on their site and even download it there as a PDF.

We had a lot to say during the pandemic about how to engage people and policymakers on science issues, and wrote about COVID-19 and pandemic communications often — check those blogs out here. I am glad to see those observations observed empirically in this survey of US adults as we have been thinking about and talking about solutions to these issues for a while. The most clear solution is for taxpayer-funded science training programs to incorporate both science policy and science communication training to help science be better able to serve Americans and build public trust. Barring that, we have tons of free resources on our site where scientists can upskill on science policy and science communication at no cost.

Scientists find facts and data more convincing than random, one-off anecdotes (which is all I’ve had to offer as a pandemic science communicator). Does that mean they will take these findings to heart? Hopefully they will find this data to be a convincing support for what we have learned in the over five years we have been a science communications and policy consulting company.

Public Attitudes toward Scientists as Communicators and Policymakers

The Pew researchers asked members of the public about their perceptions of science and scientists. Here are three graphs that stood out to me from the report. Read the full thing at Pew. If you are interested in the questions they asked, you can find a full list here.

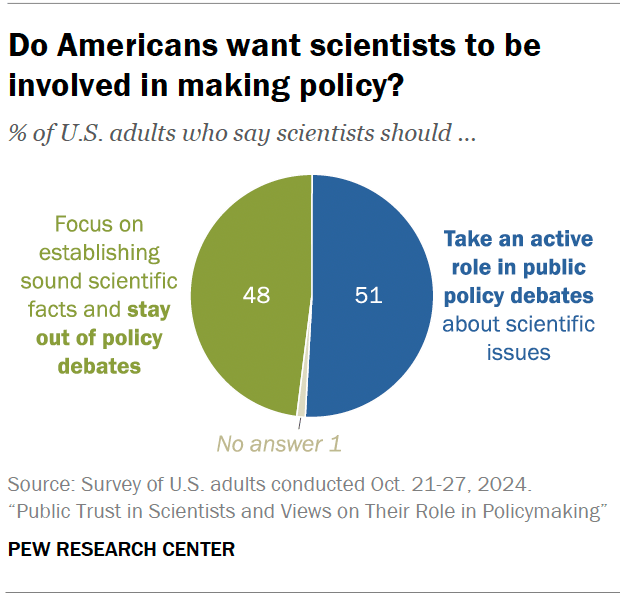

A majority of US adults want scientists involved in policymaking

The Pew researchers asked Scientists should take an active role in public policy debates about scientific issues. Here’s the question they used:

Which of these statements comes closer to your own view, even if neither is exactly right?

- Scientists should take an active role in public policy debates about scientific issues

- Scientists should focus on establishing sound scientific facts and stay out of public

policy debates

A majority — 51% — of US adults surveyed stated they’d like to see scientists involved in making policy regarding scientific issues. That is encouraging news for scientists and students of science interested in policymaking and welcome news for people like me who would like to see science policy engagement as part of taxpayer-funded science training programs!

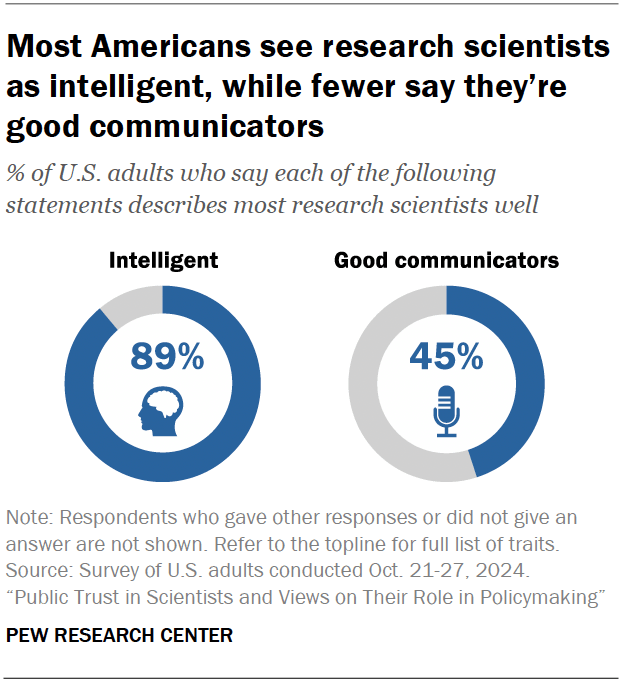

US adults believe scientists could be better communicators

Another finding from the study was that while the vast majority of US adults say that research scientists are intelligent, less than half of US adults say that scientists are good communicators. I would have loved to see Pew Research delve more into this question to ask in what ways scientists could communicate better, but let’s face it, most students do not get much structured communication training in science undergraduate and graduate programs, besides learning to write research papers and give presentations to other scientists. (Perhaps it’s a good time to drop the link to our free SciComm resources again?)

Let’s take science communication in the recent COVID pandemic as an example. While I have both on-the-job experience in science communication and have worked in Congress, most scientists do not have time to pursue these types of opportunities, since science research can be a full-time job. That is perhaps why COVID science communication did not meet my standards in the pandemic — and it is looking like it may not have met the public’s standards, either.

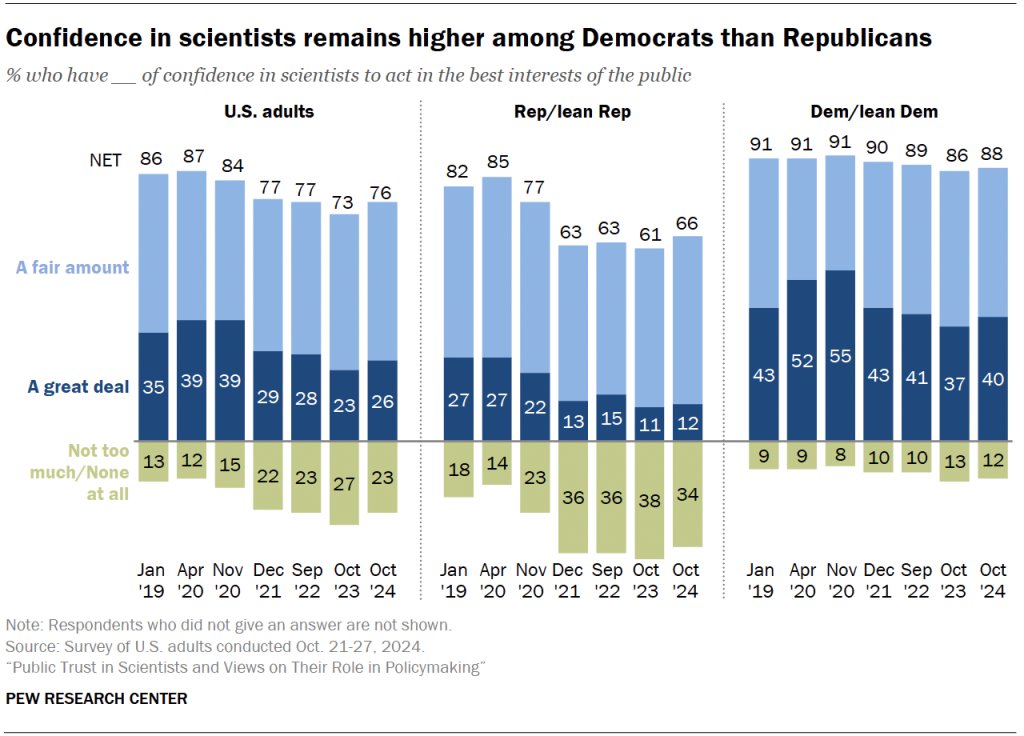

Confidence in science breaks down along political party lines

Not surprisingly, Pew Research noted the politicization of science. When it comes to confidence in scientists, Democrats are more confident about science than Republicans. The political polarization of science in the pandemic did not help this. One solution would be to communicate science in a more politically nonpartisan way, or to learn from politicians on both sides of the aisle, who have often communicated issues involving science well. I learned a lot about politicians and the ways they communicate in the 2022 midterms, working on digital communications and strategy for two winning US senate campaigns.

Politicization of science is a tough challenge because we all have political views that shape our beliefs, and they do not always agree. In the COVID-19 pandemic, would have loved to see scientists and doctors that hold Republican viewpoints and scientists and doctors that hold Democrat views agreeing on things and finding definitive areas of common ground to build trust in science as an enterprise. There were a number of issues that ended up breaking down along party lines, such as natural immunity vs. vaccines, and a number of issues that did not, but that journalists thought did (for example, vaccine uptake in red states was tied to Trump support in a news report I read, which does not make that much sense since he started Operation Warp Speed, but that became the prevailing narrative). Another tough thing about politicization of science is that sometimes when one political party says something, the other political party embraces the opposite…just because that’s how politics works.

Experts could have played a greater role here, perhaps taking the time to consider what the impacts of their expert opinions might mean for both red states and blue states, and working through the communications and crisis management aspect with a professional communicator. There never seemed to be an explanation of the science on vaccine immunity vs. natural immunity, for example, that just seemed to “stick” and resonate with everyone. That’s where politicians began to chime in with their own science-skeptical takes. For example, I will never forget the now-deleted @JudiciaryGOP tweet: “If vaccines work, why don’t they work?” To me, this question epitomized the science-vs-politics struggle.

It has certainly been a difficult science conversation with society, and the conversation has continued into the post-pandemic as Anthony Fauci and other COVID response heads have been called in to testify to the Oversight Committee’s Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic. Perhaps our nonscientist Congressional lawmakers on both sides of the aisle should have been discussing the tough questions in the COVID-19 response with the COVID “czars” all along, since they are the elected representatives for our nonscientist public, and what they say and the way they think and talk about things both influence society and are a representation of it.

Anyway, check out the full report — it’s quite interesting! If you’re interested in learning more about how to communicate science better in the next pandemic, subscribe to our blog and newsletter, follow us on YouTube and Instagram, and find us on X!

One thought on “Will Scientists Heed the Data on Public Trust in Science?”