By Santiago Gisler of Ivory Embassy

Facts alone don’t affect people’s positions in hot questions. Our evidence-based explanations bounce off their minds like bullets on Luke Cage’s torso. What if the issue has little to do with ignorance?

We are lucky to have this guest post by Santiago Gisler, scientist, science communicator, and founder of Ivory Embassy. He’s dedicated to improving science communication at the individual and societal levels to make the field more scientific, transparent, and inclusive. You may remember that Sheeva chatted with Santiago on his YouTube channel talking about bettering science communication as well as “publish or perish” culture.

Keep reading for Santiago’s reflections on the role of science communication in talking to skeptics.

A popular meme during the pandemic showed a man at his laptop turning to his wife and saying, “Honey, come look! I’ve found some information all the world’s top scientists and doctors missed.” It’s fun and can bring anyone to smirk, but it also subtly reinforces the idea that all so-called science skeptics are simply uninformed and victims of the Dunning-Kruger effect, the tendency to overestimate our knowledge. But how accurate are these beliefs?

I hadn’t met many religious people until I started the Biomedicine Bachelor’s program at university. That class swarmed with religious students, some skeptical of evolution and natural selection—mind you, we studied biomedicine.

I especially remember having a loud discussion about natural selection with two religious friends during a study session ahead of a creeping physiology exam. I was baffled, unable to connect how two of the most intelligent people in the class rejected the notion of slow, adaptive changes in organisms and their populations. Even my references to the fast adaptations of the bacteria we’d cloned during our recent microbiology lab sessions went over their heads. They accepted the bacterial adaptations but couldn’t link them with human development.

This mental puzzle stuck with me so much that I now retell the story almost 20 years later when discussing skepticism and science.

Most of us have experienced that facts alone don’t affect people’s positions in hot questions. Our evidence-based facts bounce off their minds like bullets on Luke Cage‘s torso. This brazen rejection of reasonable, scientific facts may convince us that lack of knowledge is the true perpetrator and that we should ignore these ignorant science skeptics.

But what if the issue has little to do with ignorance? In that case, it’s partially our responsibility as scientists and science communicators to approach these groups differently, especially if we want to persuade them.

The science communication paradox

We’ve never in history had as much knowledge about how to reduce existential dangers as today and still disagreed so much about scientific facts. Law professor and science of science lecturer Dan Kahan refers to this phenomenon as the “science communication paradox.” He says this paradox happens in societies where open debate and free speech are encouraged.

Nowhere in the world is the science communication paradox as explicit as in the United States, but we find it almost everywhere. People’s views of risks like global warming, gun ownership, or fracking often depend on their political or cultural beliefs. Those aligning with liberal ideas tend to see these as high risks, and those aligning with conservative views label the same as low risk.

The science of science communication focuses on resolving this paradox and developing strategies to address the root cause of public disagreement on scientific issues.

Researchers—and many social media users—have argued for some time that the public, having limited scientific literacy, fails to assess risks as scientists do. The argument goes that scientists approach risks consciously, through empirical evidence and analytical thinking, while the public confronts them with unconscious emotions.

This prevalent perspective on the public’s tendency to misalign dangerous risks is known as the public irrationality thesis (PIT). Its supporters argue that if people learn more about science, they’ll see risks like global warming the way scientists do.

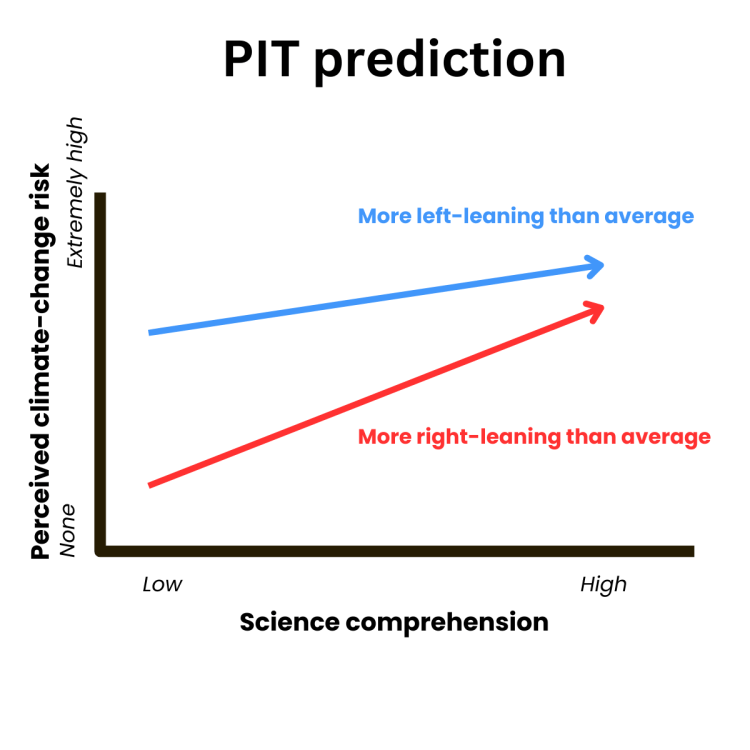

Here’s the prediction Kahan details about the PIT, depicted in graphical form. It illustrates what the PIT predicts on the topic of climate communication: that risk perceptions of climate change between left- and right-leaning groups would converge as their scientific understanding increases.

It turns out that real life doesn’t follow the PIT. Although we assume that the gap between risk perception narrows as we learn more about a topic, the opposite happens. As we become more knowledgeable about science, we tend to adhere more to our ideologies and become more polarized—the gap widens.

Here’s another graph I’ve modified from Kahan’s essay that shows that phenomenon. It illustrates the trends observed when comparing levels of science comprehension and political alignment.

It’s almost as if another factor than scientific literacy influences how we view science-related risks: an ideologically-motivated reasoning. In other words, our motivational biases and emotions affect how we view new knowledge.

Let’s assume we identify as science communicators with a vital responsibility in society to disseminate science and improve the world. Our motivational reasoning would reflexively reject any studies suggesting science communication fails to impact people’s science knowledge!

The same thought process occurs when the public becomes confronted with evidence associated with societal disputes. We tend to reflect on polarizing information in ways that align with our group’s identity, such as moral values, political beliefs, or social norms. The cultural cognition thesis (CCT) suggests that people’s cultural values and group identities shape how they view or interpret risks, facts, and evidence on controversial topics.

Kahan, who supports CCT, suggests that people with strong scientific knowledge and reasoning are better at using evidence to support their beliefs—even when those beliefs don’t align with scientific consensus. He writes, “the most science-comprehending members of opposing cultural groups, my colleagues and other researchers have found, are the most polarized.”

In other words, if we look back to my university years, we could argue that it was not that my two religious friends were scientifically illiterate. They had more scientific knowledge than most, which they fitted into their religious beliefs. Their scientific knowledge even served them to protect this worldview, finding gaps in my arguments, exceptions in science, and alternative interpretations that aligned with their beliefs.

We see this play out in research by Kahan and colleagues. When religious and non-religious individuals answered scientific questions, the distinction between the two groups’ answers varied depending on the questions. Individuals with high scientific knowledge from both groups knew that nitrogen makes up most of the Earth’s atmosphere and that electrons are smaller than atoms.

The answers from the groups diverged only when questions tested participants’ cultural or political identity. The scientifically knowledgeable individuals in the religious group scored far lower than their non-religious counterparts when answering if humans developed from earlier species of animals.

Disentangling the science communication paradigm

My work aims to improve science communication and, as an extension, scientific literacy among the general public. But why even bother if scientific literacy makes the public more skilled at defending their in-group’s opinion? It seems to be a dead-end mission.

Maybe it’s my motivated reasoning kicking in now, but enhancing science communication and scientific illiteracy still makes sense. The insights about the science communication paradox offer us more than a binary answer. Just as people’s beliefs and knowledge vary, exchanges between a communicator and audiences are nuanced and context-dependent. Solving the science communication paradox requires nuanced strategies, which complicates things for those accustomed to hammering every problem as if it were a nail.

Kahan suggests that the new science of science communication can use the so-called disentanglement principle to reduce the science communication paradox. The disentanglement principle helps separate facts from ideas that might challenge an individual’s cultural or political identities. Using neutral messaging and emphasizing common goals, we can avoid identity-motivated opposition, according to this principle.

Communicators and policymakers using the disentanglement principle don’t argue against petrol use; they argue for job opportunities in the renewable energy industry. And they advocate for a society that includes seniors and children rather than pushing for masks or vaccines.

Expanding on the disentanglement principle

The disentanglement principle can help us separate knowledge from identity, but it has received criticism regarding its practical implementation or empirical validity. Political identities and ideologies are so dominant in the scientific discourse that disentangling these from knowledge is impossible for science communicators alone.

We can also question how easy it is to mask political intentions using the disentanglement principle. We can assume that the public eventually realizes the Trojan horse is shaped as new job opportunities, senior-friendly projects, or rapidly adapting bacteria. And we’ll have quite some serious cleaning ahead of us once those cats are out of the box.

Although these challenges exist, they don’t cancel out Kahan’s ideas—they just show how complex science communication can be. These ideas can engage us to adapt our content based on our target audience and purpose. We can use several tactics that have successfully informed us about climate change.

For example, the social judgment theory suggests starting with ideas our audience already agrees with, rather than bombarding them with facts. Speaking to someone critical of humans’ impact on global warming can argue that reducing air pollution benefits health and the environment. The social judgment theory aligns tightly with the disentanglement principle, but the social judgment theory emphasizes framing based on the audience’s current beliefs. The disentanglement principle breaks down complex issues to find common ground.

And I know storytelling probably became saturated with the last two decades of non-stop stories about storytelling, but narratives work. Audiences tend to enjoy stories or narratives. We consume stories constantly, such as films, books, and documentaries. We’re more willing to accept opinions or value judgments when someone presents them as stories rather than through purely logical, fact-based arguments.

And if none of those tactics work, how about setting an example and committing to reporting science-related issues transparently and as unbiased as possible? Science communicators and journalists should try to honestly reflect all sides of important stories that impact people’s lives, regardless of political alignment or affiliation.

Science skepticism doesn’t happen in a vacuum. If scientific distrust becomes a societal problem, we must critically evaluate why those voices gain traction. We can’t just call them ignorant; that’s an unfair and incomplete explanation—it’s unscientific.

Santiago Gisler is a science communicator, coach, and former molecular biologist who runs IvoryEmbassy.com and the YouTube channel @IvoryEmbassy. Santiago helps individuals and organizations communicate science more effectively through coaching, workshops, and content creation, emphasizing scientific and critical thinking.