By Sheeva Azma

What if society normalized scientists working in Congress?

I think that we should.

Have you, as a scientist, or person with a science background, ever considered working in Congress?

I mean, like, really considered working there: being a nerdy scientist amidst a sea of politicians and poli-sci and government majors (as I once was).

What’s been holding you back? (If there is anything specific, I’d love to know – reach out to me here.)

For me, one thing that held me back from working in Congress was what felt like a lack of opportunity. There was never enough information on how to actually get a job there for people like me, with a science background; in fact, some internships in policy I’ve seen exclude people who major in science, in favor of people with political science, government, journalism, and other backgrounds. It also didn’t help that my friends, who were avid consumers of news, didn’t have the same passion for policy that I did.

What if society normalized scientists working in Congress?

I think that we should.

In my work at Fancy Comma, I have talked to numerous people with a science background, and even provided advising on resumes and cover letters, for people with science and tech backgrounds looking for jobs in Congress. I do this work because working in Congress is one of those things that is rarely advertised as a job that scientists can do, but one that is sorely needed.

If you want to get an idea of the scale at which we elect scientists to Congress, CNN celebrated the addition of seven scientists to both the House and Senate in 2018. That’s seven people out of over 500 total serving in Congress, or just over 1% of the whole federal lawmaking body.

If you’ve been interested in working in Congress but you never knew how to get started on that big, lofty goal, this blog is for you.

We have written a lot about getting involved in science policy on the Fancy Comma blog. Here, I recap everything we’ve written about working in Congress so far here on the Fancy Comma blog.

Congress’s Functions and Constitutional Authority

Congress is the first branch of government detailed in the Constitution, right after the Preamble, established by Article I.

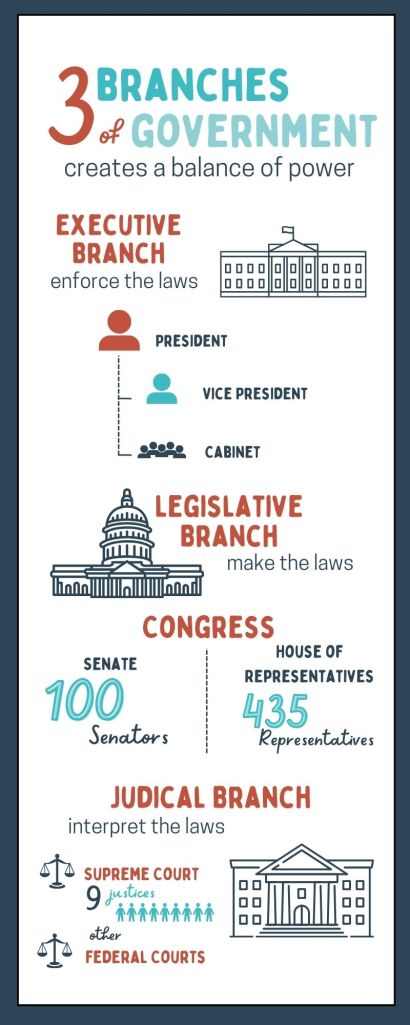

The United States Congress is composed of the House of Representatives, which is a large body with elected officials that are proportionate to a state’s population, and the Senate, which allots each state two Senators. As of writing this blog, there are 100 senators in the Senate, and 435 representatives, and 6 non-voting delegates, in the House, according to Wikipedia. The non-voting delegates can make speeches but cannot vote and represent American Samoa, District of Columbia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and United States Virgin Islands.

Checks and balances was a system enshrined in our Constitution to make sure that no one branch of our government is more powerful than any of the others. We’re focused on the legislative branch (Congress) here, but remember that there are two other branches of US federal government: executive branch (that’s the president) and judicial branch (that’s the Supreme Court).

Some of Congress’s functions include:

- Making laws

- Representing and supporting their constituents

- Informing the public about national issues

- Controlling federal spending

- Maintaining checks and balances of the other two branches

(By the way, this image is from elementary school teacher Carlee Guzman on Canva. Fun!)

Functions of Congress unique to it, and not shared with the judicial or executive branches, include:

- Legislative Authority: Congress is the only branch with the power to create, amend, and repeal laws. While the executive branch can issue regulations and the judiciary interprets laws, only Congress can enact legislation.

- Declaration of War: Congress holds the exclusive authority to declare war, a power not shared with the president or the Supreme Court.

- Control of Federal Spending: Congress has the “power of the purse” in government – to originate revenue bills (in the House of Representatives), approve budgets, and allocate federal funds through appropriations bills.

- Advice and Consent Role: The Senate uniquely provides advice and consent on presidential appointments and treaties. This includes confirming federal judges, the president’s cabinet members, and other high-ranking officials.

- Impeachment Power: Congress can impeach and try federal officials, including both the president and the Supreme Court justices. The House initiates impeachment proceedings, while the Senate conducts trials.

- Oversight Function: Congress oversees the implementation of laws by executive agencies, investigates misuse of federal funds or abuses of power, and gathers information to inform new legislation.

The Constitution gives Congress the power to collect taxes, as well, via enacting federal tax law, which is handled by the House Ways and Means Committee, and its counterpart in the Senate, the Senate Finance Committee. These committees also deal with Congress’s ability to regulate commerce with foreign countries, which is a power not unique to Congress but also shared with the president.

This is just a brief overview of what Congress does – if you are interested in any of these or other functions Congress deals with, I suggest you take a look at reports from the Congressional Research Service – which are the comprehensive reports that Congress itself uses to make decisions on important issues.

Working in Congress as a Scientist

If you’re interested in working in Congress as a scientist, you can find answers to frequently asked questions here and here.

We’ve written a guide to interning in Congress as well as a short white paper on working in Congress as a staffer with a science background.

Networking is key to working in Congress, especially for scientists, who often do not have many people in their own social circles employed in the US federal legislative branch. Informational interviewing can be a key tool – learn more about it here.

If you’re interested in electing someone to Congress, check out our guide to campaign staffer positions.

If you’re not interested in working in Congress, but would like to keep in touch with lawmakers, this guide can help you.

Lastly, you can check out my mukbang series on each branch of the US federal government.

The Bottom Line

There are not nearly enough scientists in Congress to tackle all of the issues lawmakers face involving science – including agriculture, health, national security, transportation, high-tech manufacturing and commerce, federal research funding, and innovation policy, to name a few. We scientists must be the change and get more involved in our federal policymaking or pay the price of being excluded from it because we failed to make our voices heard.

2 thoughts on “Would you take your science background to Congress?”