By Toby Shu

In the wake of Loper Bright, scientists should understand that their expertise has been devalued.

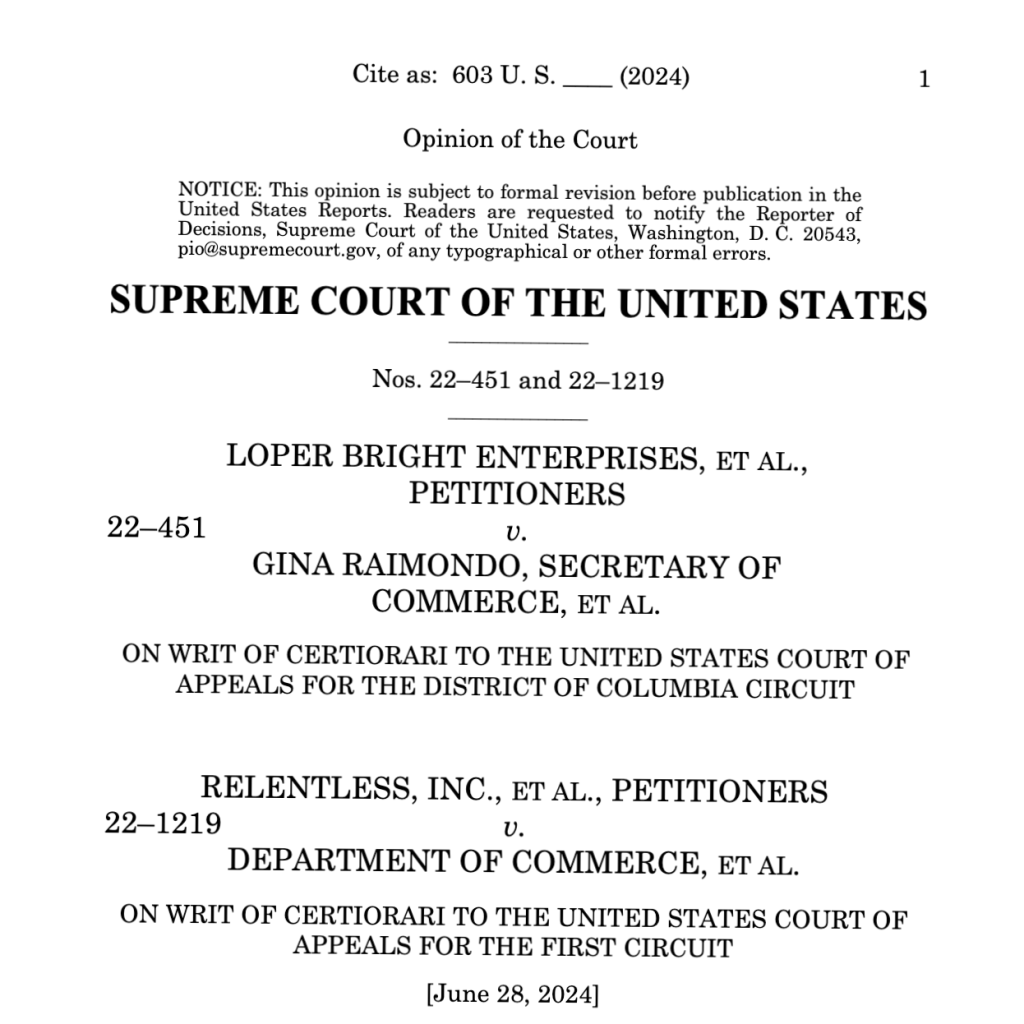

In 2024, the Supreme Court overruled its 40-year-old decision in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. by a 6-3 vote. In doing so, the Court has shifted policymaking power away from scientific experts. In this post, I aim to describe Chevron, the decisions overruling it—Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce—and how they impact and devalue the role of scientific expertise in our federal government. I take no position here on the correctness of Chevron, Loper Bright, or Relentless as a matter of law.

Chevron

Back in 1984, the Supreme Court decided the case of Chevron v. NRDC. The case posed an innocuous question: whether the term “stationary source” in the Clean Air Act of 1963 refers to the components of a factory (such as a new smokestack) or a whole factory. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had held the former view, but changed its interpretation to the latter view under President Reagan, and the NRDC, an environmental group, challenged the changed interpretation.

The Court, in a 6-0 decision written by Justice Stevens, held that federal courts should defer to agency interpretations of statutes (that agencies are implementing) if the statutes are (1) ambiguous and (2) the agency interpretation is reasonable. They took the view that Congress, composed of representatives—not experts—drafts legislation with goals and permissible means to achieve them, while executive agencies, staffed by experts, implement them. The Court reasoned that Congress, in delegating authority to agencies, necessarily provided the power for “the formulation of policy and the making of rules to fill any gap left, implicitly or explicitly, by Congress.” Therefore, when agency rules were reasonable, agency determinations were due deference. The judiciary, on the other hand, was not supposed to weigh in on policy issues—as the Court stated, “The responsibilities for assessing the wisdom of such policy choices and resolving the struggle between competing views of the public interest are not judicial ones.” Overall, experts in the executive branch, not courts, would determine how to gloss statutory ambiguities. By virtue of this reasoning, the Court ruled against the NRDC and upheld the EPA’s new interpretation of the Clean Air Act.

Loper Bright and Relentless

While Chevron was originally seen as relatively minor, it grew in prominence over time and gained notoriety, as courts applied it in an enormous number of cases. Justice Neil Gorsuch railed against it when he was a federal appeals judge on the 10th Circuit. Conservative jurists argued that Chevron deference was an unlawful abdication of the judicial branch’s responsibility “to say what the law is.”

Further, Chevron allowed for agency flip-flopping as administrations would change. For instance, under the Telecommunications Act, if internet service providers (ISPs) are “telecommunications services,” they are subject to more stringent regulation by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), but if they are “information services,” they are not. The FCC had initially understood ISPs to be information services, but it reversed course under President Obama, declaring them telecommunications services. Then, under President Trump’s first administration, The FCC switched back, reclassifying ISPs as information services, and under President Biden, ISPs were switched again to telecommunications services. In other words, the FCC reversed its “expert” opinion 3 times in 10 years in a partisan way. During the first two flips (under Obama and Trump), Chevron was the law of the land, and the DC Circuit deferred to the change in agency understanding after each flip.

The Court agreed to hear Loper Bright and Relentless in 2023 on the question of whether Chevron should be overruled. The two cases were consolidated, meaning they asked the same question, the Court heard their arguments together, and the court delivered an opinion for them together. Both cases involved the National Marine Fisheries Service’s interpretation of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act that required Atlantic herring fishery boats to bring aboard and pay for observers to ensure compliance with regulations. However, the Supreme Court took the cases to resolve the question about Chevron, and did not specifically resolve the question of statutory interpretation.

In 2024, the Supreme Court overruled Chevron by a 6-2 vote in Loper Bright (Justice Jackson was recused, as she had heard the Loper Bright before the DC Circuit) and 6-3 vote in Relentless (hereafter referred to collectively as Loper Bright). The majority, written by Chief Justice Roberts, held that Chevron could not be reconciled with the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) mandate that a “reviewing court shall decide all relevant questions of law, interpret constitutional and statutory provisions, and determine the meaning or applicability of the terms of an agency action.” They argued that courts often have to resolve ambiguities to reach a best answer, and statutes empowering agencies were no different. As the Court stated, “In the business of statutory interpretation, if it is not the best, it is not permissible.” Further, the Court argued that Chevron was incompatible with the fact that “Judges have always been expected to apply their “judgment” independent of the political branches when interpreting the laws those branches enact.” In the case of expertise, they explained that agency experts have no expertise in resolving statutory ambiguities. Instead, courts have the expertise necessary to resolve legal ambiguities—that’s their entire job!

Justice Kagan wrote for the dissent. In responding to the majority, she began by asking what kinds of questions Chevron was actually being used to resolve. She gave a list of examples (I have simplified them here), citing prior cases:

- “When does an alpha amino acid polymer qualify as such a ‘protein’? Must it have a specific, defined sequence of amino acids?”

- “What makes one population segment ‘distinct’ from another? Must the [Fish and Wildlife] Service treat the Washington State population of western gray squirrels as ‘distinct’ because it is geographically separated from other western gray squirrels? Or can the Service take into account that the genetic makeup of the Washington population does not differ markedly from the rest?”

- “[For the purposes of Medicare reimbursements to hospitals,] How should the Department of Health and Human Services measure a ‘geographic area’? By city? By county? By metropolitan area?”

- “[With regard to reducing aircraft noise over the Grand Canyon,] How much noise is consistent with ‘the natural quiet’? And how much of the park, for how many hours a day, must be that quiet for the ‘substantial restoration’ requirement to be met?”

These questions, she argued, should clearly be understood as questions of expertise (such as the case of understanding squirrel populations) and/or questions of policy tradeoffs (such as the case of reducing aircraft noise over the Grand Canyon), not questions of law. She agreed with the majority that courts are suited to answer questions of law, but noted that Chevron deference applied only when “a court trie[d] to divine what Congress meant, even in the most complicated or abstruse statutory schemes” and concluded that it “[could] not do so.” Regarding the argument about the APA, she noted that the language (provided above when discussing the majority) does not force courts to review regulations without deference—in fact, the “relevant questions of law” could be decided when a court finds a statute ambiguous. Thus, the APA “neither mandates nor forbids Chevron-style deference.”

Justice Kagan also lambasted the majority for failing to respect precedent. By directly overruling a 40-year-old case, and undermining the reasoning of an enormous number of cases that applied Chevron, the Court introduced large amounts of instability into the system. (The majority responded by stating that due to tinkering, Chevron was never stable enough in application to produce meaningful reliance on the decision.) Further, Justice Kagan argued, the Court undermined Congress, which had passed laws in the interim with the understanding that deference would be given to agencies—in fact, Congress considered legislation several times to overrule Chevron and explain agency regulations should be reviewed, but the legislation failed.

Implications

Regardless of the correctness of Loper Bright, it is clear that the ruling has shifted power away from executive branch agencies and given it to the courts and a dysfunctional Congress. In understanding the role of scientific expertise in our system, it is undeniable that this is a loss for scientific experts. This is because the executive branch is uniquely able to staff and institutionalize experts that represent a field in our government of three branches. While there is no doubt that scientists have a part in shaping legislation as it goes through Congress, it is also undeniable that representatives are largely not scientists, and are not as able to craft sound scientific policy as agency experts. Similarly, while scientists can appear as expert witnesses in courts or file amicus (friend of the court) briefs, scientists may appear on both sides of an argument, presented as equal experts due to the presence of think tanks and other interest groups, when in fact, scholarly consensus clearly rests on one side. (It also should be noted that in Loper Bright, the vast majority of scientific amici wrote against overruling Chevron and lost, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Public Health Association.) Executive agencies were one of the most direct ways for scientists to shape policy before Loper Bright. For creating good, science-backed policy, the existence of a team of experts who stay on staff and pursue their research in an institution like the NIH is invaluable.

Now, this is not to say that the expertise in the executive branch is by any means infallible, as we have seen with both the flip-flops discussed above and in the Trump administration’s firing of vaccine experts. Expertise obviously can be (and has been) manipulated within the executive branch, and political decisions can be passed off as stemming from expertise instead of politics. Nevertheless, it is simply wrong to think that Congress can address science policy minutiae better than executive branch experts, or that courts are better able to judge good science than actual scientists.

In the wake of Loper Bright, scientists should understand that their expertise has been devalued, and seek to engage more in civic processes to counteract that. They should assert their will as civically engaged voters who will write to representatives from the county level all the way to the federal level in favor of science-backed policies and urge legislatures to pass laws that allow experts to answer difficult scientific questions.

Toby Shu is a rising sophomore at Georgetown University seeking a BS in Mathematics and History. Toby is interested in constitutional law, the history of science, and the growing capabilities of artificial intelligence in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

One thought on “Loper Bright: an Explainer for Scientists”