Table of Contents:

Introduction

Structured Inequality

COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death

Minorities and Health Care Access in the COVID-19 Pandemic

– Access to Primary Hospital Care

– Access to Healthcare Insurance

Unemployment

Conclusion

Introduction

[back to menu]

The novel coronavirus has swept across the United States, leaving no one sheltered from the looming threat of COVID-19, regardless of age, socioeconomic status, gender, or race. However, the impacts of COVID-19 have been uneven. Racial disparities are evident in the COVID-19 pandemic not only in infection, hospitalization, and death rates, but also in the economic and psychological impacts of stressors related to the pandemic and social distancing. Why is this? The answer lies in the structured racial and ethnic inequalities that permeate the facets of life and institutions in the US.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare just how far the racial and ethnic inequalities in the US reach. In this blog, I will discuss the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on minority populations — both in terms of the health impacts as well as associated economic impacts. Let’s first discuss structured inequality or structural racism in more detail.

Structured Inequality

[back to menu]

Structured inequality, also called structural racism, refers to the collective economic, social, political, and legal inequalities experienced by minority groups. Structural racism is “structured” in the sense that it is rooted in and carried out through the institutions and everyday experiences that make up the fabric of US life. Because it is ingrained in our institutions, structural racism persists across generations. It is most obvious in income and wealth inequality, which stands as the key determining factor in life opportunities and well-being.

COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death

[back to menu]

The COVID-19 impacts on minority populations reiterate the structural inequalities faced by minority populations. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), Native, Black, and Hispanic/Latinx individuals in the US experience significantly higher instances of COVID-19 infection and hospitalization and higher rates of COVID-related deaths than their white, non-Hispanic (NHW) counterparts.

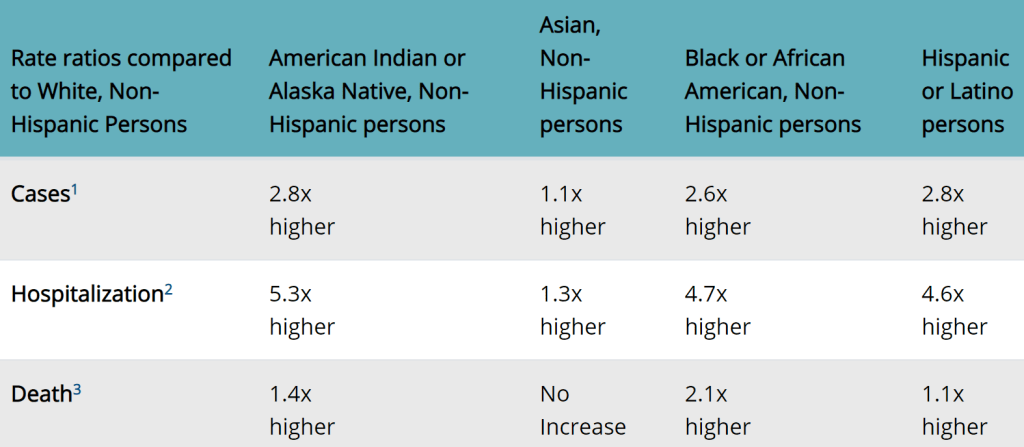

Here’s a table from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that breaks down COVID-19 case counts, as well as hospitalization and mortality rates, by race:

As the table above demonstrates, the racial disparities evident in COVID-19-related mortality rates paint a bleak picture of health inequality. Latinx and Native individuals are most likely to develop COVID-19, followed closely by Black individuals. Native individuals have the highest chance of being hospitalized due to COVID-19, at a rate 5.3 times higher than that of NHW folks. Black, Non-Hispanic individuals have the highest chance of dying from COVID-19 — at a rate that is more than double that of NHW populations.

Comorbidities including heart disease, obesity, and diabetes exacerbate COVID-19 severity. These comorbidities are more prevalent among Black, Native, and Latinx individuals. Black individuals are more likely to be obese, which can worsen COVID-19 outcomes. Another notable statistic is that the rate of diabetes among Native individuals in the US is twice that of NHW and higher than any other racial or ethnic group, which may explain the high hospitalization rate in Native individuals. Diabetics are more likely to have severe complications if they contract COVID-19.

Minorities and Health Care Access in the COVID-19 Pandemic

[back to menu]

Minorities face an increased risk of severe COVID-19, as well as barriers to health care in a non-pandemic setting, including both barriers to primary hospital care and health insurance.

Access to Primary Hospital Care

[back to menu]

COVID-19 has not only infected more individuals than the flu, it has also led to a higher rate of hospitalization and death from infection than the flu this year. Access to primary hospital care – and specifically, COVID-19 tests and treatments – are paramount for individual and society-wide safety. Thus, access to medical care is the first and most significant line of defense to avoid and abate serious complications of a COVID-19 infection.

Access to Health Care Insurance

[back to menu]

Health care providers have worked to provide coverage for COVID-19-related health care, such as COVID-19 tests and in-hospital care for severe COVID-19 cases. Without insurance, these costs can quickly add up. Therefore, access to health care insurance is also very important in the COVID-19 pandemic. Access to health insurance, when broken down by race, also shows major disparities. For example, Native individuals have the highest number of uninsured, with an estimated rate of 2.8 times that of NHW and Asian individuals.

While all members of the 574 federally-recognized US tribes are technically eligible for health coverage at Indian Health Institute (IHS) facilities, this coverage does not include Native individuals who are not enrolled tribal members, or those who are enrolled members of unrecognized tribes. Further, IHS statistics indicate that only a fraction of those who are eligible for service are actually served by these facilities.

The insurance situation is not much better for other minority groups. Hispanic/Latinx individuals are uninsured at a rate of about 2.4 times that of NHW and Asian individuals in the US. Black individuals in the US are uninsured at a rate of about 1.5 times that of NHW and Asian individuals in the US. As these numbers illustrate, there are very clear disparities in access to health insurance that exacerbate the minority impact of COVID-19.

Disparities in health, including health literacy and health care access, have exacerbated the disproportionate minority impact of COVID-19. Of course, these disparities are not new to the pandemic. Nor are they unique to health.

Unemployment

[back to menu]

Beyond COVID-19’s health impacts, the virus has caused international lockdowns which have stifled economic productivity worldwide. Structural racism can also be observed in the subsequent furloughs and layoffs which occurred in the ensuing months since COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in mid-March 2020. In April 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, the overall U.S. unemployment rate was 14.5%. However, the racial disparity in unemployment affected Latinx the worst (at 18.2% unemployed), followed by African-Americans (16.6%), and Asians (13.7%). The racial group with the lowest unemployment rate was whites — the only racial group coming in below average at 12.8%.

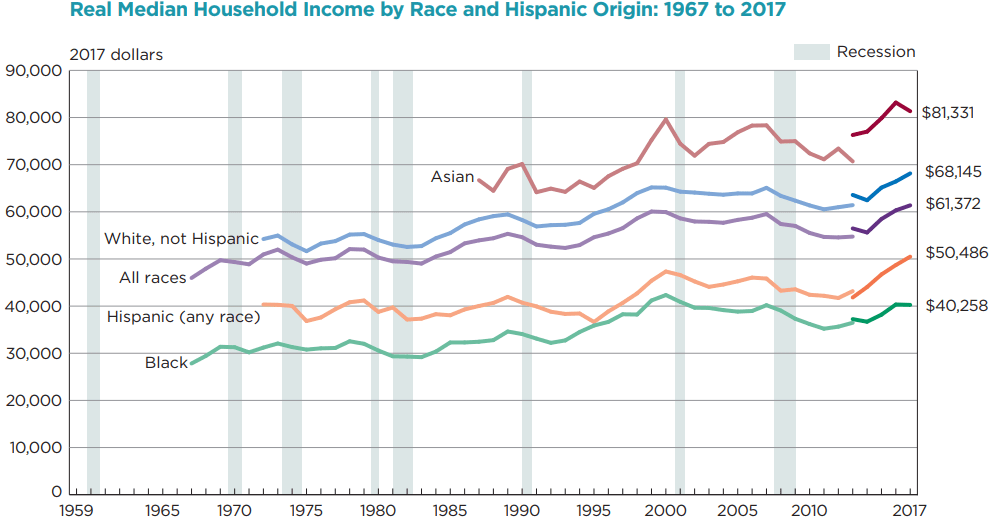

Racial/ethnic disparities in the US derive from systemic stratification (persistent group-level society-wide structural inequalities) by race/ethnicity and are therefore not isolated to one life setting or outcome. The effects of racial/ethnic inequality in one arena are diffuse; they have a cascading effect on all other contexts. As such, it is not surprising that the racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infections and outcomes mirror the existing disparities in indicators of economic well-being.

Income is one of the key indicators of both general well-being and social inequality. Black individuals in the US make 60% of the income of NHW and Asian individuals in the US. The proportion is the same for Native individuals compared to NHW and Asian individuals. This number is slightly better for Hispanic/Latinx individuals, who make 75% of what NHW and Asian individuals make, on average.

As for poverty, 2.2 times as many Black individuals live in poverty as compared to NHW or Asian individuals. This number is roughly the same for Native individuals, with 2.3 times as many Native individuals living in poverty as NHW and Asian individuals. Finally, Hispanic/Latinx individuals fare just slightly better than Black and Native individuals, with two times as many Hispanic/Latinx individuals living in poverty as NHW and Asian folks in the US.

Conclusion

[back to menu]

Minorities experience disparate health outcomes, and this fact has only been magnified in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death rates among Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and indigenous (Native) communities bring into stark relief the deep-rooted and diffuse nature of structured inequality in the US. There are also disparities in economic impacts of the pandemic, as well as psychological impacts which, though I have not discussed them here, are very real. Finally, though we have grouped Asian individuals and NHW together in this discussion of racial disparities, it’s important to recognize the negative impact of racism on Asian individuals in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health outcomes, like many other quality-of-life and opportunity outcomes, are merely indications – windows – that illuminate the insidious and diffuse nature of structural inequalities in the US. Racial and ethnic inequalities are certainly not confined to the US, many of the inequalities experienced by Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and indigenous communities in the US are paralleled across the globe. In order to understand these health outcome disparities experienced by minority populations, it is necessary to view these disproportionate negative outcomes in the context of systemic racism — inequalities which coalesce to create barriers to social, psychological, and physical well-being.

One thought on “Structural Racism and Health Disparities in COVID-19”