(Alternative title: “How NOT to Communicate Science”)

By Sheeva Azma

Fancy Comma provides science communication (SciComm) mentoring and training among our many services, and you know, sometimes, a good way to learn how to do something is to learn how NOT to do something. Keep reading to learn more about ethical science communication by learning about different examples of unethical communication in SciComm!

Learn how NOT to communicate science in this post. #SciComm

Tweet

Public-facing science communication is one type of SciComm. In public-facing SciComm, scientists seek to raise awareness, understanding, and enthusiasm of science among the general public. There’s also inward-facing SciComm, in which researchers communicate science to each other. The channels of communication between scientists and society ideally flow freely.

With all of this communication, however, comes a challenge. It’s important to communicate ethically in science, and that’s where the sub-discipline of SciComm comes in. We’ve previously blogged about six types of unethical communication, and in this post, we provide examples of each in the SciComm realm. Our hope is that, by reading this blog, you can work to identify unethical science communication and avoid it and even speak up against it. Let’s work together to make SciComm a space of good-faith conversation, in which people do not mislead with false narratives and deception. We already experienced so much misinformation and fake news in the COVID-19 pandemic, and it unfortunately cost many lives.

Understanding unethical SciComm is part of developing science literacy so that you can critically analyze science in the news, for instance, or on social media. Keep reading to learn some examples of unethical communication in SciComm to be able to spot it and avoid it!

Navigation menu:

Communication Ethics Lessons from Superheroes

What Are the 6 Types of Unethical Communication?

Examples of Unethical Communication in Science

#1: Destructive SciComm

#2: Coercive SciComm

#3: Manipulative-Exploitative SciComm

#4: Deceptive SciComm

#5: Secretive SciComm

#6: Intrusive SciComm

Hire the Science Communication Experts at Fancy Comma, LLC

Communication Ethics Lessons from Superheroes

There are actually many forms of unethical communication situations. Some unethical communication seeks to misinform and mislead. Other types of communication do not adhere to ethical standards because they are plagiarized. Yet other communication forms hinder civil or political rights.

In a nutshell, ethics in communication relates to the ways we yield our pen as communicators. As Spider-Man once said, “with great power, comes great responsibility.” As a superhero, he understands the challenges of being a force for good and using one’s power and influence responsibly. In fact, both Spider-Man (Peter Parker) and Superman are also journalists – the former is a photojournalist for the Daily Bugle, and the latter is a writer for the Daily Planet. Check out a take on Superhero Journalism Ethics from WNYC’s “On the Media.”

What Are the 6 Types of Unethical Communication?

For our previous blog, we created a helpful infographic, which you can download here, to explain the six types of unethical communication:

We talk a lot about how to communicate science. In this post, we’re talking about how not to communicate science. Ready to learn more? Keep reading!

Examples of Unethical Communication in Science

#1: Destructive SciComm

Destructive communication seeks to tear down people or organizations. It can take the form of character assassination, prejudice, or slander. Destructive communication criticizes and involves character attacks. You could say that the opposite of destructive communication is constructive communication, which seeks to preserve a good relationship between the communicating parties while providing helpful feedback. I mentioned “destructive SciComm” in the title, but given that I’m talking about the loud anti-science voices out there in the world, maybe I should have titled this section “destructive anti-SciComm”?

As we’ve previously blogged, W.C. Redding, known as the father of organizational communication, first discussed these six types of unethical communication collectively in his 1996 paper. The goal of his paper was to tell organizations to start paying attention to ethics.

Redding defined destructive communication as “insults, derogatory innuendoes, epithets, jokes (especially those based on gender, race, sex, religion, or ethnicity); put-downs; back-stabbing; character-assassination; and so on.” In the pandemic, these forms of communication were often directed to healthcare and science professionals. Being a science communicator in a pandemic is hard.

Destructive communication such as name-calling and personal attacks made SciComm dangerous for many high-profile science communicators. Anti-science opportunists utilized the pandemic and the global science literacy problem to gain power and influence at the expense of society. They insulted scientists and healthcare professionals in an attempt to legitimize anti-science as a “movement.” This became a huge challenge for SciCommers, and led to people’s deaths through ignorance. One of the most sad things in the pandemic for me was seeing the interviews with people in the hospital suffering from severe COVID who said that they wished that they hadn’t listened to the anti-science naysayers in the world. To me, it was a tangible negative impact of destructive anti-science communication, which included personal attacks on scientists and healthcare professionals.

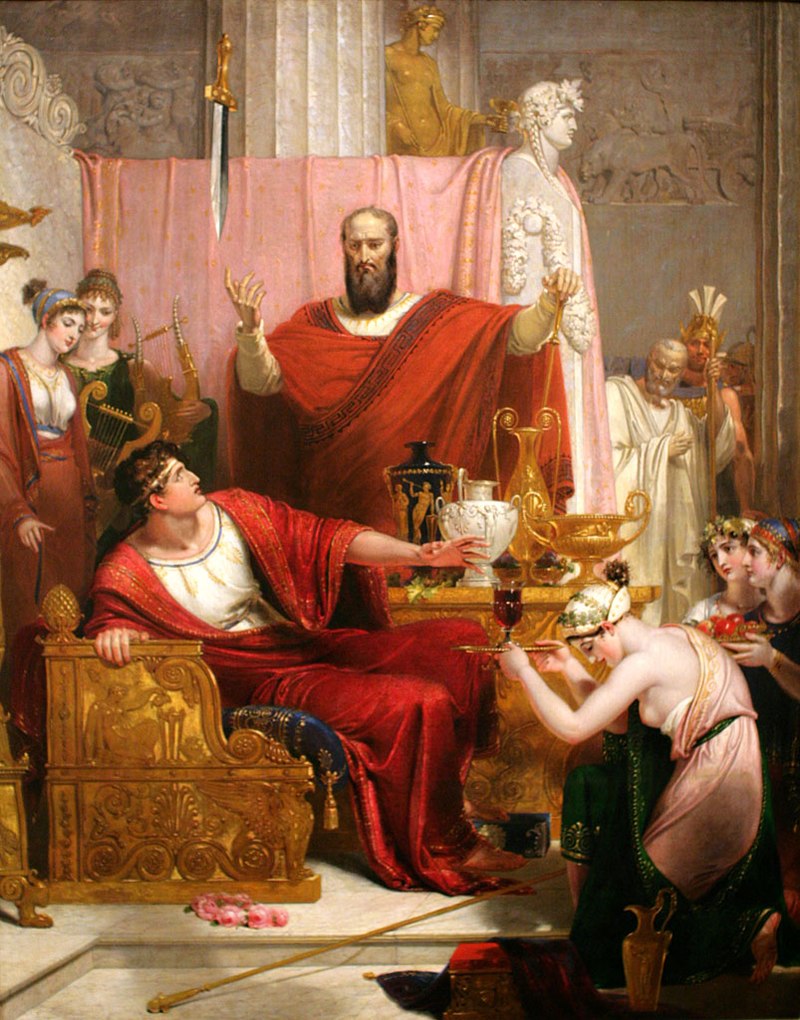

The National Academies, the collective scientific academies of the United States, report that “scientists and health professionals have been subjected to threats and other attacks – online and offline – resulting from their efforts to combat the spread of COVID-19 with public health interventions and information.” Examples of destructive SciComm in the pandemic include verbal attacks against the healthcare and scientific communities, including high-profile SciCommers such as Dr. Peter Hotez of Baylor University, Dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine and Co-Director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development. Dr. Hotez says in the National Academies report that he faced so much verbal abuse, including anti-Semitic attacks, that he needed protection from law enforcement. “You’re doing this [public communication of pandemic science] feeling like you’re doing this with the sword of Damocles over your head, said Dr. Hotez in an interview with the American Medical Association. In mentioning the sword of Damocles, Dr. Hotez alludes to the persistent peril faced by those in positions of power. Dr. Hotez blames others in power – namely, politicians – for much of the destructive communication tactics, including those stemming from political polarization, that he has endured as a scientist.

#2: Coercive SciComm

Coercive communication intimidates and threatens to achieve a purpose. Redding defined coercive communication as “communication events or behavior reflecting abuses of power or authority resulting in (or designed to effect) unjustified invasions of autonomy.”

Examples of coercive communication include threats or implications of firing or defunding, or excluding people and/or groups from important discussions. Another example is sending contradictory messages or creating no-win or dead-end situations. Even refusing to listen can be a form of coercive communication.

Redding defined three subcategories of coercive communication that we can look for to root out unethical SciComm: these include message ambiguity (causing doubt or uncertainty for the audience), double bind (contradictory demands with no positive solution), and denial of ability to respond.

I constantly see examples of coercive communications in the political world, and it was no different in the pandemic. In the COVID pandemic, everyone needed to learn science quickly to understand the challenges of our daily lives, and nobody agreed on the right way to do so. SciCommers butted heads with each other and with other important people like political officials. Both sides refused to listen to each other, believing they were each right. Oh, how I wished we could all have a normal conversation and try to find common ground as a red state SciCommer. All of us in society have different beliefs and values, but we talked over each other, creating small groups rather than being able to empathetically have discussions and find common ground. I like to think that we’re still working on that, and that SciCommers such as myself are learning from the things that went wrong in the pandemic, to communicate better for the next time (if there is a next time).

#3: Manipulative-Exploitative SciComm

Manipulative-exploitative communication, as its name implies, manipulates and exploits its audience’s ignorance, prejudice, and/or fears. This type of unethical communication often takes the form of fear mongering. I find fear mongering to be a lazy, ineffective form of SciComm.

The weird part is that I actually saw a lot of fear mongering as a tactic to get people to care about COVID science and get a COVID vaccine, for instance. Someone even Tweeted at me once to tell me that fear mongering is a winning SciComm and health communications strategy. I completely disagree – when you scare people to try to get them to do something, you’re ignoring the role of communication in the first place. People wanted answers to their curiosities about the vaccines – specific reasons and evidence, not fear mongering. Nobody likes to be manipulated into doing something. It might work for some people, but it is a terrible way to build a relationship with your audience. So, yeah…fear mongering as SciComm is a no from me. I much prefered talking to people and figuring out what their concerns are for pandemic SciComm, and addressing those directly.

#4: Deceptive SciComm

Deceptive communication is misleading on purpose. It may not include the full story or use half-truths to achieve its goal of deceiving its audience. I like to think that science as an enterprise is anti-deception because it is about finding out new things about the world. However, science can also deceive, even if it’s not on purpose. Just think about all of those people trying to stay relevant amidst a “publish or perish” nature who fabricate data, overstate the implications of their results, and generally try to be sensationalist to garner media coverage, for example. I’m not saying that all scientists do this, but sadly, people have told me some horror stories.

It’s sad that ethics sometimes goes out the window as a way to stay relevant and successful in the scientific enterprise. Sadly, having to wade through all of this deception slows down science, which has implications for the people in our world. Just check out this list of retracted papers that were initially published in the pandemic. They probably weren’t all retracted due to being outright lies, but they didn’t pass academic standards, and got published anyway. Science has a way of legitimizing anyone who can manage to work the system to their benefit, and that is a form of deception in science (and SciComm), even if it’s accidental.

The opposite of deception is transparency. It can be difficult to admit the shortcomings of your science or SciComm, but it’s a good practice to avoid misleading and confusing people, and consequences of that later on down the line.

#5: Secretive SciComm

Secretive communication tries to sweep information “under the rug.” As scientists, we thrive on truth and data, so SciComm does not readily lend itself to such avoidance. However, organizations that have such secretive communications do not always do so overtly or seemingly deliberately.

Redding defines secretive communication as “job requirements or work conditions that mandate employee silence at pivotal points in work relationships or meetings; establishment of routines and culture of silence.” While scientists do not overtly work to silence each other, there is a culture of silence in academia about work abuses. Abusive supervisors, racism and sexism, and other aspects that make science toxic get swept under the rug often. Sometimes, the reason is that the people who make academia toxic are at the top of the food chain. Other times, it is because people are afraid to speak out for whatever reason. As I have previously blogged, science doesn’t happen in a vacuum; this means that whatever toxic abuses continue in the academic science enterprise actually decide the kinds of science that happen and do not happen.

Obviously, the solution is to speak out against injustice in science and SciComm, but people who do so often face backlash. According to the National Whistleblower Center, most people who act as whistleblowers end up losing their jobs. Sadly, this just serves to make science culture even more toxic.

#6: Intrusive SciComm

A great example of intrusive communication is the Paparazzi, who are those photographers that follow around famous celebrities and try to capture all of the details of famous people’s daily lives. Redding defines intrusive communication as “messages of surveillance, usually hidden, that breach another’s privacy rights.”

An example of intrusive communication at an organization is searching through an employee’s files, phone messages, and other correspondence. Intrusive communication reveals a lack of trust between the organization and the employee. To combat intrusive communication, organizations must work to respect the boundaries of their employees, without barging in too much with communications, according to healthcare strategist Kathryn Nardozza.

Respecting the privacy of individuals is important from an organizational standpoint, and it is also important in science and science communication. Nudgespot, in a Medium post, details communications they received that they found both intrusive and non-intrusive. Repeated text messages, emails that are not targeted, and communications that are both too frequent and don’t address the intended audience can be seen as intrusive. So, as a science communicator, work to know your audience before communicating, not to communicate for the sake of communication.

Hire the Science Communication Experts at Fancy Comma, LLC

Are you looking for guidance in your science communication endeavors? We offer SciComm mentoring and training services. Check out our SciComm mentoring and training services, or visit our Services page to see all the ways we can help you in science communication.

6 thoughts on “Unethical Communication: Examples from Science and SciComm”