By Sheeva Azma

On November 13, 2025, Adriana Bankston, PhD, a former staffer in the office of Rep. Bill Foster (D-IL-11), gave a talk to the Genetics Society of America entitled “From the lab to the legislature: How researchers can impact science in Congress.”

In her talk, Adriana explained the many ways scientists can get involved in public policy as well as her own path to public service, namely working in Congress for a year as the first person to hold the Congressional science, technology, and policy fellowship (STPF) now offered by the American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy.

The challenge: crafting evidence-based policy

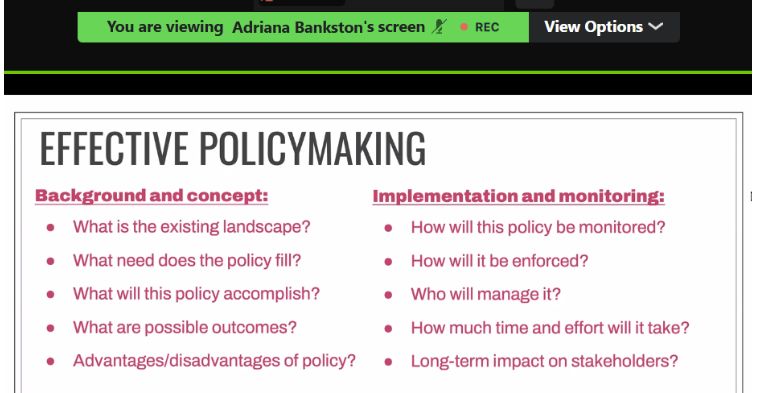

The goal of making policy more evidence-based is a complicated one, according to Adriana. It is the “product of multiple inputs, mechanisms, and interactions,” she says, involving many different entities that operate in different ways.

How do you get all of those different parts to work together?

Policy work is collaborative, involving consensus, making decisions with limited information and resources. It involves building consensus, making decisions collectively using limited resources and imperfect information, and is pluralistic in nature, Adriana explains.

Pluralism means that many different groups bring their unique interests and viewpoints to the table, working together to influence government policy decisions. This means that there are many competing groups vying for Congressional attention, but the power, in policymaking, is distributed among various factions rather than being concentrated in a single group. As a result, the policy outcomes resulting are a product of negotiation and compromise among these competing interests.

If that sounds tough, that’s because it is! Members of Congress are bombarded by a lot of information, Adriana says, and Congress does a lot of things.

Adriana’s general framework for shaping policy

“There is a broader framework here,” Adriana explains about policymaking: identify the problem, who can fix it, and the best way to act, and you’re good to go.

If only it could be that simple in execution. “There is a lot of thought process that goes into how to actually engage with Congress,” she notes.

In terms of creating policy, Adriana says, the world is your oyster. Policy happens at think tanks, society, non-profits, university, Congress…and more. You can do it through research, writing reports, trainings highlighting how to engage researchers in advocacy, and even work on the Hill, as she has done.

Adriana outlined some mechanisms of policy action in Congress: legislation, briefings and events, and speeches. It was nice to hear a science metaphor (“mechanisms of action”) in a discussion of science in Congress, since so few scientists inhabit that space.

Adriana herself got into science policy after completing her PhD in biochemistry at Emory University. She has previously focused her policy work on raising postdoc salaries, which was work done in collaboration with a small nonprofit. “Starting small is a good idea,” she says. She worked for years with the University of California in government relations, where she lobbied Congress on research priorities, contributed some legislative language for the CHIPS and Science Act to include postdocs and add language on artificial intelligence.

The audience to this discussion had several insightful questions, such as the following question someone asked in the seminar:

Q: Who does Congress go to when they want to learn about science issues?

Adriana: All the things: scientific societies, university government relations offices, think tanks. It’s kind of on you to build that connection and look them up and find out what they are working on and try to pitch your ideas. They do like to hear from students who have been impacted by the administration, all that, which is really spearheaded by student groups coming to our office…there’s all these different ways [to get involved].

What does one do working as a Congressional staffer for a scientist elected to office?

What does one do as a staffer in the office of a scientist elected to public office? It turns out that the answer to this depends on the lawmaker’s portfolio, and in this case, Rep. Foster, as a scientist in Congress, had a heavily STEM-focused portfolio. So that’s what Adriana worked on.

Adriana’s “really cool and very busy” (in her own words) policy portfolio — the topics she handled — included research, science and technology, STEM education and immigration, energy and environment, space, and the Research and Development Caucus with which Rep. Foster is involved.

She showed a slide that had a sampling of the legislation and letters she worked on. She also helped write Rep. Foster‘s speech at the Stand Up for Science rally held in Washington, DC on the National Mall.

The above slide is actually just a sampling of a subset of her work! “This is only a few things; there were a lot more bills,” she says. Also, as she noted, lot of these bills have outsider endorsements from various organizations.

Attending Congressional briefings and hearings helps keep you up-to-date on the issues, and Adriana did that. Sounds like she was kept quite busy!

Writing letters to the White House was another thing she got to do in her year in Congress working in Rep. Foster’s office. She got to write to the Trump Administration about how Congress is unhappy with all these folks from the National Science Foundation getting fired. “It’s hard to know if the letters worked,” she says of that effort, but to her, the importance was the “messaging” that “it’s more “messaging” that “Congress needs to be doing these things.” Writing the White House in response to executive action is something Congress routinely does, she shared.

She helped organize briefings in DC with advocacy groups with Research & Development caucus. It was a good way to have conversations about science and get the word out that Congress is having these conversations. To her, the caucus was a great way to have conversations on important topics in science that nobody else in Congress was having. “And, again, it’s bipartisan,” she stated of the R&D Caucus.

She also discussed her meetings with constituents – she met with students from MIT, Virginia, Emory and showed pictures of them alongside their concerns. “It was really exciting to be there and hear concerns and try to include them.”

Adriana also wrote speeches for Rep. Foster on the House floor “which is something useful to Congress to show support for science and young scientists,” she said.

After talking for a bit, Adriana turned the tables and asked: what works to communicate with lawmakers?

I said I called my lawmakers recently. “I keep calling my [members of Congress] on various issues but I feel like the interns are not really listening, LOL. Are they? I am frustrated with the way our government is right now,” I wrote in the Zoom chat.

She said that her office picked up every phone call and did listen.

“I really liked Hill day,” said one audience member: “It felt like you were actually getting somewhere by speaking to someone face-to-face.”

“I’ve been told that Hill days and letters are appreciated, but it does really feel nebulous to me what works,” commented another seminar attendee.

How do we get lawmakers to actually act on science?

In connecting with lawmakers, know that it’s not a one-time thing; you will need to provide ongoing support and feedback and hopefully you can build a relationship with them where you become a trusted source of information.

To do that, you first need to be able to explain your publicly funded-research, what is known about it, and what purpose it serves, both inside and outside of the lab.

You’ll also need to research the member(s) of Congress you are speaking to beforehand and learn about their priorities, voting record, and the committees on which they serve — and how they make decisions and use information. Understanding and highlighting benefits from your work to their constituents (bonus points if you are their constituent) also goes far.

Understand the federal budget process, including appropriations, is crucial in this process. So, too, is developing a message that is “clear and compelling” and resonates with policymakers.

“All of these things are working to some extent, even if we don’t see the benefits right away,” said Adriana. “Some of these are practical things you do to set up for next steps for the future.”

Keep the relationships going, Adriana states. One Hill day is good, but “making sure that you keep going to them is useful, and again, this is a long game.”

Another key in meeting with lawmakers is to be prepared to adapt. Hill day meetings with a Congressional office can be 5 minutes or 30 or 50. You might not meet with the actual person in office, but with one of their staffers, who does most of the legwork in the office. If you are meeting with the actual lawmaker, they may have to cut the meeting short to go vote. One time, I was meeting with my representative (Chair of Appropriations) during budget season, and we had to meet outside of the House office in the hallway because they were so packed!

Coming up with an elevator pitch can be a good first step when preparing to meet with lawmakers. As you come up with a standard elevator pitch, adaptability is key, and preparing for the different scenarios can help. Having different versions of your pitch is good and you should tell them right off the bat why it’s important. Adriana shared a helpful elevator pitch guide developed by communication researchers at MIT.

What role can people with a science background play in Congress in our current time?

I asked Adriana what she thought was the role of scientists and science-informed people in our current time, and what Congress can do at the current time when the executive branch keeps usurping the power of the purse.

Her answer?

- Messaging from the Congressional office on why they support young scientists

- Trying to include the views of scientist staffers like herself on various things that Congress is already doing and highlight that. Adriana’s efforts were highlighted by a lot of media outlets, too, suggesting that they will be more visible than non-scientist efforts in Congress.

- “When you’re a [political] minority [in Congress], you can do less things, but you can still do something.”

- “Everyone can input into this large policy web, where you are and from where you are, whether you are in Congress or not.”

We next did an elevator pitch exercise in which attendees tailored Congressional members to the people who will hear them, and including a specific policy ask. The session concluded with me asking Adriana about the role of Congress in AI.

According to Adriana, “it is an ongoing discussion.” In the House, there was a task force created last Congress about the big issues going on with AI in healthcare, national security, education, and more, and they created a big report, and there should be a few bills coming out soon implementing those. She advised: “if you’re targeting someone [to talk to in Congress] for AI legislation, a lot of folks are leading on that, so try to figure out who that is.” She also recommended following the AI task force, and to follow the work of staffers covering AI in terms of what bills are moving and so on.

As for whether the House task force AI report can be trusted, Adriana says that “staffers that cover AI wrote that report; probably, they did also solicit input from scientists but it is well-resourced.”

All in all, we learned a lot from Adriana about how to be an agent of change in Congress. “Thank you for sharing your experience with us. It is really cool to hear what it was like from inside these offices,” said one attendee.